Enter the Dystopia

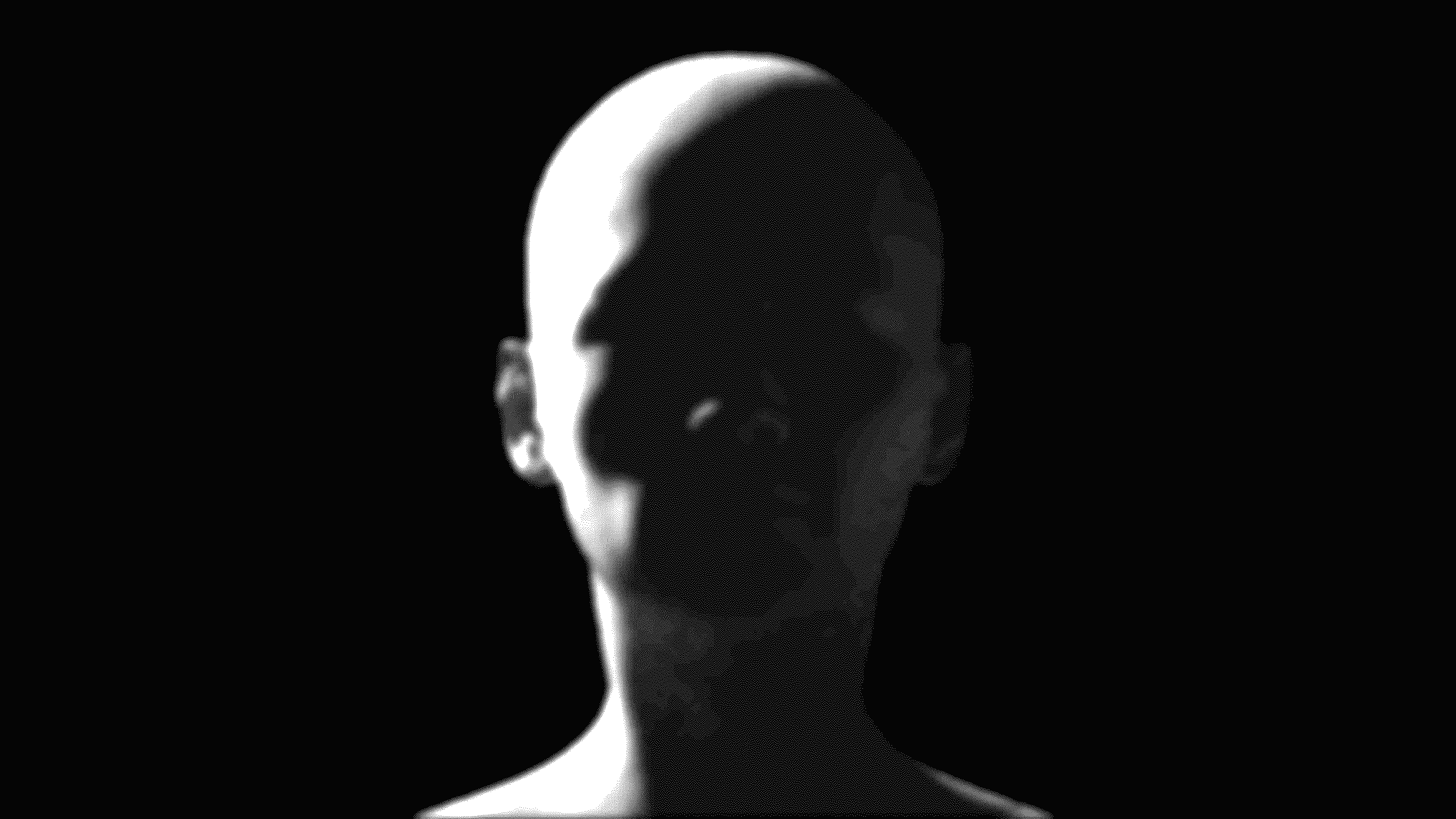

Dr. Breen addressing Gordon Freeman

I'd like to take a moment to address you directly, Dr. Freeman.

Yes. I'm talking to you, the so-called One Free Man. I have a question for you. How could you have

thrown it all away? It staggers the mind. A man of science, with the ability to sway reactionary and

fearful minds toward the truth, choosing instead to embark on a path of ignorance and decay. Make no

mistake, Dr. Freeman. This is not a scientific revolution you have sparked...this is death and

finality.

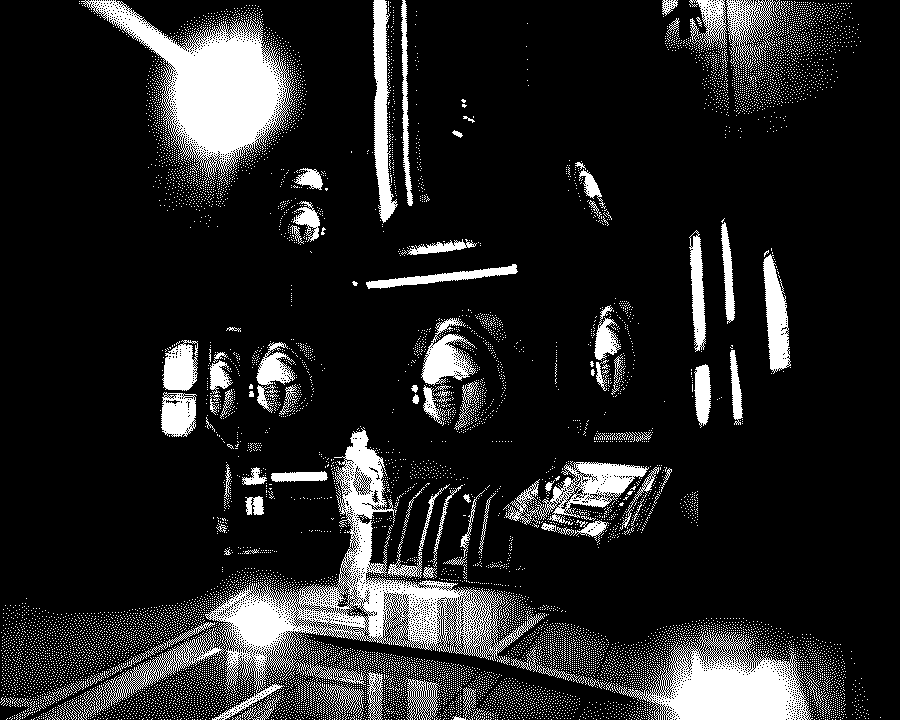

Dr. Breen welcoming Citizens to City 17

Welcome. Welcome to City 17.

You have chosen, or been chosen, to relocate to one of our finest remaining urban centers. I thought

so much of City 17 that I elected to establish my Administration here, in the Citadel so

thoughtfully provided by Our Benefactors. I have been proud to call City 17 my home. And so, whether

you are here to stay, or passing through on your way to parts unknown, welcome to City 17. It's

safer here.

Dr. Breen on Gordon Freeman

Allow me to address the anxieties underlying your concerns, rather than try to answer every possible

question you might have left unvoiced. First, let us consider the fact that for the first time ever,

as a species, immortality is in our reach. This simple fact has far-reaching implications. It

requires radical rethinking and revision of our genetic imperatives. It also requires planning and

forethought that run in direct opposition to our neural pre-sets.

Dr. Breen addressing the Overwatch

This brings me to the one note of disappointment I must echo from our Benefactors. Obviously I am

not on the ground to closely command or second-guess the dedicated forces of the Overwatch, but this

does not mean I can shirk responsibility for recent lapses and even outright failures on their part.

I have been severely questioned about these shortcomings, and now must put the question to you: How

could one man have slipped through your force's fingers time and time again? How is it possible?

This is not some agent provocateur or highly trained assassin we are discussing. Gordon Freeman is a

theoretical physicist who had hardly earned the distinction of his Ph.D. at the time of the Black

Mesa Incident. I have good reason to believe that in the intervening years, he was in a state that

precluded further development of covert skills. The man you have consistently failed to slow, let

alone capture, is by all standards simply that--an ordinary man. How can you have failed to

apprehend him?

Dr. Breen on collaboration

This brings me to the one note of disappointment I must echo from our Benefactors. Obviously I am

not on the ground to closely command or second-guess the dedicated forces of the Overwatch, but this

does not mean I can shirk responsibility for recent lapses and even outright failures on their part.

I have been severely questioned about these shortcomings, and now must put the question to you: How

could one man have slipped through your force's fingers time and time again? How is it possible?

This is not some agent provocateur or highly trained assassin we are discussing. Gordon Freeman is a

theoretical physicist who had hardly earned the distinction of his Ph.D. at the time of the Black

Mesa Incident. I have good reason to believe that in the intervening years, he was in a state that

precluded further development of covert skills. The man you have consistently failed to slow, let

alone capture, is by all standards simply that--an ordinary man. How can you have failed to

apprehend him?

Dr. Breen to Gordon Freeman

Tell me, Dr. Freeman, if you can: you have destroyed so much — what is it exactly that you have

created? Can you name even one thing?... I thought not.

Exploring Virtual Dystopias

A study of architectural stagecraft and narrative in video games. Case study: Valve’s Half-Life 2

At the 2007 Game Developers Conference in Lyon, independent art director Viktor Antonov, who

art-directed and did concept design for the award-winning Half-Life 2, discussed how visual

design

in games can accomplish so much more than a sales-driving pretty package -- the game world can

be a

powerful tool for storytelling, and with that in mind, Antonov presented his lecture on

meaningful,

visual design in games. "The topic today is sort of abstract," admitted Antonov as he began.

"It's

more about defining... the design process and visuals and the story for a game — and I think

that

[applies to] everyone on a game.”

Visual Design vs. Graphics

Antonov pointed out that there can be a great deal of confusion about what is graphics and what is

art

direction. "Nowadays there’s a general consensus that visuals are just as important as anything else

in

a project because if it looks good, it will sell," he said. "Everyone happens to agree — which was

not

the case a few years ago.

Gameplay was more important, or engine was more important." He continued, "The misinterpretation that happens in production, oftentimes in production teams, is that managers and project leads often perceive visual design as a packaging design for the product. They’ll say, we’ll have the game, game dynamics, gameplay, we’ll make it pretty, and people will like it and consume it.” “I’ve seen this in production," Antonov added. "A project is planned, and then a 'coating' of art is applied. I’d like to step back to a point, and change this perception if possible.”

Gameplay was more important, or engine was more important." He continued, "The misinterpretation that happens in production, oftentimes in production teams, is that managers and project leads often perceive visual design as a packaging design for the product. They’ll say, we’ll have the game, game dynamics, gameplay, we’ll make it pretty, and people will like it and consume it.” “I’ve seen this in production," Antonov added. "A project is planned, and then a 'coating' of art is applied. I’d like to step back to a point, and change this perception if possible.”

Invisible Storytelling

Asserted Antonov, “Visual design is actually a tool for communicating; visual design has a different

function than packaging and selling the product.” He had one key point to stress about visual

design:

"It’s really, really strongly linked to the story, whenever there’s a strong story present in the

game.”

This could mean using shapes and symbols to tell a story similar to the way letters and words are

used

to compose a written narrative.

Visual design can also comprise emotional information, or rational information. Explained Anton, “In a well designed game, every little piece has a meaning... skillful storytelling is invisible storytelling.” He added, "Games are consumed through the eyes, and are a visual medium. They should use the language of the eyes, and not have a story pushed on them.”

Visual design can also comprise emotional information, or rational information. Explained Anton, “In a well designed game, every little piece has a meaning... skillful storytelling is invisible storytelling.” He added, "Games are consumed through the eyes, and are a visual medium. They should use the language of the eyes, and not have a story pushed on them.”

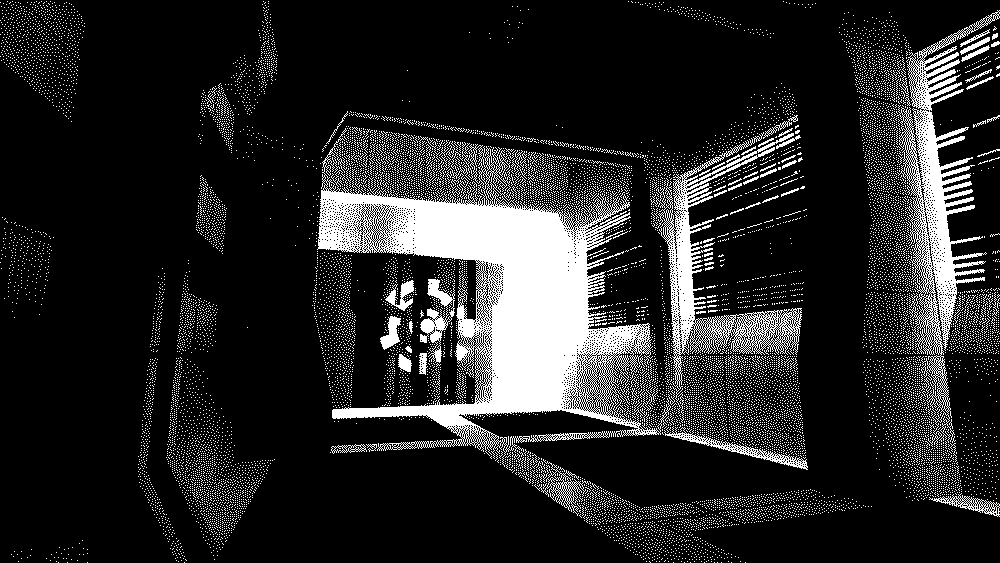

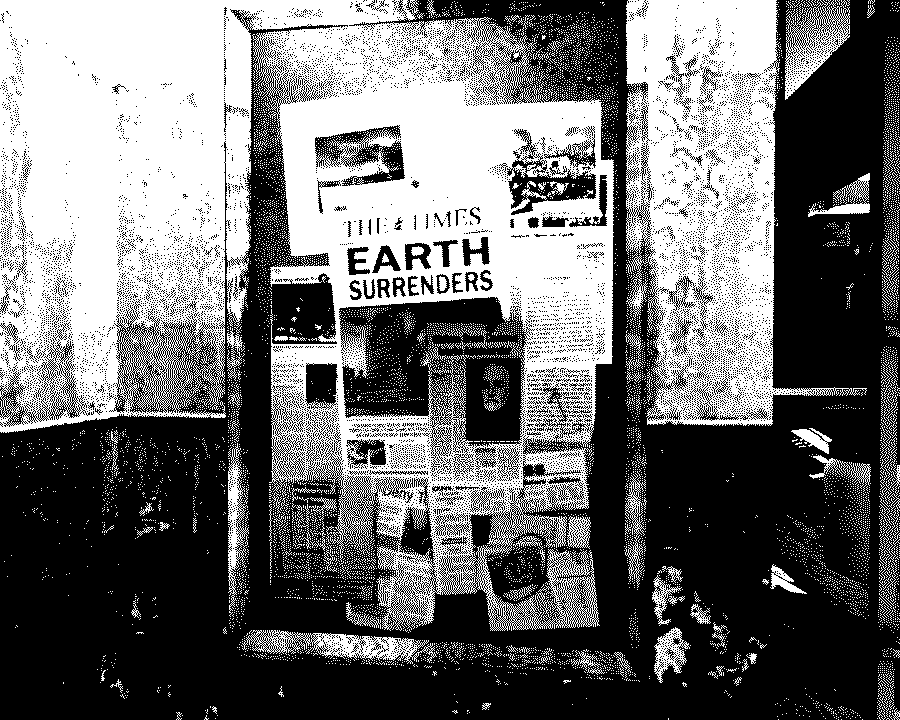

Realism

Antonov advised discussing realism early on in a project -- not photorealism, but the internal logic

of

the game world. “When you invite a player to play a game, show him you’ve mastered the medium enough

to

convince him of anything," he noted. And Anton illustrated how sometimes creating realism can hinge

on

what the visual designer leaves out -- "like a good photographer," he said. He talked about starting

with a banal, boring world at the start. “The more you do that, the most science-fiction you can

sell

later.” He showed a screenshot of a building, with a common-looking texture. “In cold weather,

people

use double windows,” he explained, pointing out how modeling the game's double windows took little

effort, but added more depth and realism to the world with one simple texture tweak.

But that’s not what we’re after.” He

opined

that there should be some slightly off-putting or disturbing elements. A prime example, for Antonov,

is

the film Rosemary’s Baby, where a key scene is blocked from view by a doorway. Without these sort of

strategic images, Antonov said, a game can simply become "decorative art." Finally, he talked about

how

players appreciate art that took this much effort. He recalled seeing *Half-Life 2* testers running

quickly through a level and not looking at the level’s art work and thinking, "well, there’s a

year’s

worth of work wasted." Concluded Antonov, “You can’t really predict how people will react, but you

can

sometimes do the opposite: you can attract them in a certain direction."

In "Half-Life 2", he explained, they tried to have some of the monsters not in halls, but outside on

beautiful autumn days. He cited the Stanley Kubrick film Barry Lyndon -- set against gorgeous

landscapes, but with cruel, tiny people. “Let’s not forget, a game is a series of images,” he added.

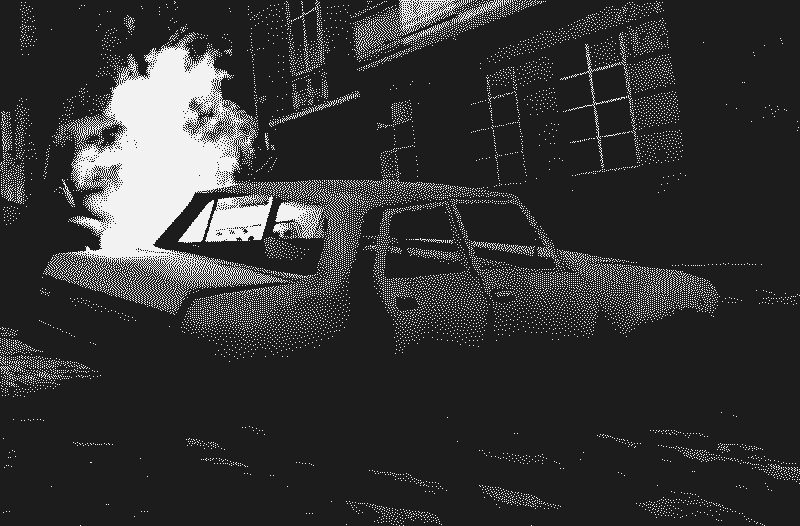

Creating Contrast and Form

“If you have a chance to do that, turn it into black-and-white,” he continued. “I always start with

the

idea that every image needs an even distribution of darks and lights.” He continued, “Even more

abstract, we can give out information through the language of form.” He talked about the difference

between horizontal and vertical, calling the horizontal "very normal," while, “there’s something

frightening about the vertical.” He talked about one project that featured cylinders. “Choose a

theme of

form, and stick to it,” he said. "When you’re picking a theme, you can ask yourself, ‘what do I want

to

do?’ Then you have all these tools to achieve that." Good looks may not be the essential goal, as

Antonov illustrated: “Technically, a post-card looks good.

But that’s not what we’re after.” He

opined

that there should be some slightly off-putting or disturbing elements. A prime example, for Antonov,

is

the film Rosemary’s Baby, where a key scene is blocked from view by a doorway. Without these sort of

strategic images, Antonov said, a game can simply become "decorative art." Finally, he talked about

how

players appreciate art that took this much effort. He recalled seeing *Half-Life 2* testers running

quickly through a level and not looking at the level’s art work and thinking, "well, there’s a

year’s

worth of work wasted." Concluded Antonov, “You can’t really predict how people will react, but you

can

sometimes do the opposite: you can attract them in a certain direction."